After a short drive we pull off the road and up to a small portable cabin. The thin guy asks for my passport. Again, I find myself fumbling in my rucksack.

“Don’t worry, take your time.”

Probably due to exhaustion, this is the first time I am conscious of being concerned. No one puts you in a car, asks for your passport, and tells you to take your time unless they’re intending to take you somewhere you don’t want to be. For a long time. But no clearer thought comes into my head other than “They’ve got me”. At this stage I have no idea either of who “they” might be. The thin guy gets out, opens my car door and shows me to the cabin. The only light outside is from the passing trucks.

Hamdy’s car pulls up and the two men emerge, the joy I heard in their voices only thirty minutes ago now drained from their faces. Hamdy looks serious, resigned; Mohsen very concerned. I give them only the briefest of glances. Partly I don’t want to look conspiratorial. But neither can I look them in the eye. It feels useless to speak. What can I do – apologise? Ask what’s happening? No. It’s pointless. In the darkness we just have to let events take their course.

I get into the hut first. A kindly-looking mustachioed man in camouflaged trousers and a T-shirt with “ARMY” on it, stands by a desk. He puts a red plastic chair in front of him and beckons me to sit. Mohsen walks past me and sits almost opposite, and Hamdy takes a seat to the right of me but just out of view. Conversation begins in Arabic, throughout which I cannot make out much more than repeated mention of the word ‘arabeya’ (car). At 7.09 a call comes in from Jenie; the reception is not good but I can tell she is worried. Before breaking up I am only able to give her the briefest details of my situation. As the other men talk I pick up my phone and compose a WhatsApp message to my wife: “Pauline I’m fine but am just having to answer some police questions. I will get back to you as soon as I can xx”. I am relieved, and reassured, when the calm reply comes straight back: “OK xx”.

I ask if I can have a cigarette and Mohsen goes back to the car to get his packet of Rothmans. I’m not sure whether this is to give me something to do while the men are talking, to calm my nerves, or because it’s what you would do in a film. I am too tired, and adjusting quickly to events, to make sense of either my thoughts or emotions. The army guy asks if I would like tea and the thin guy goes to get it. I sit there dragging on the cigarette, exhausted. The conversation between the army man, Mohsen and Hamdy continues uninterrupted. After some ten minutes or so, Army man asks me, in broken but reasonable English, what I was doing in the desert.

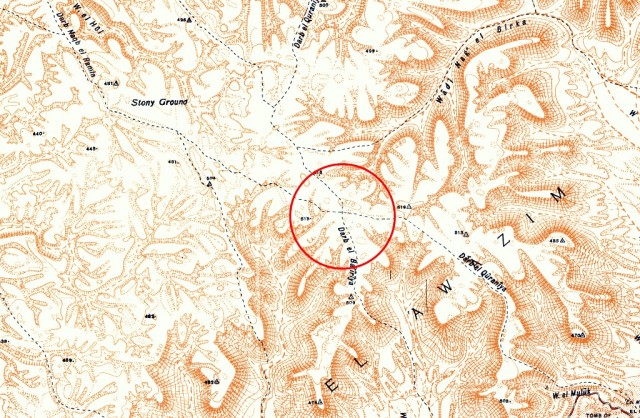

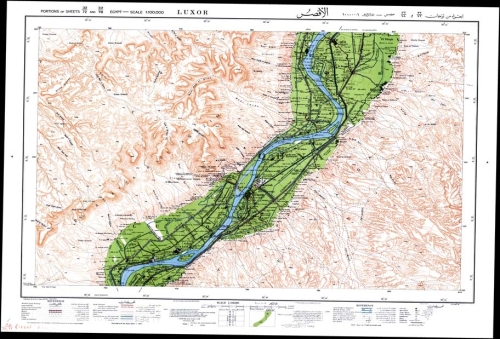

I tell him that I was “walking across the bend”. He informs me that the desert is ‘a military area’. That’s news to me. I say “sorry” and then attempt to follow this up with Arabic, but instead of “Ana aasif” (I’m sorry) say “Ana aarif” (I know). I am immediately aware of my mistake and resolve to keep to English. I catch Mohsen’s eye and he gives me a quizzical look. I further resolve to say as little as is required in case I contradict anything the two cousins have already said.

I’m conscious that I am unable to look at Hamdy, partly because he is out of my direct line of sight. But mainly because I am starting to feel faintly sick at the thought that I might have fucked up both of their lives, and those of their families – for what trivial, selfish purpose? I glance at my passport on the table and the two Egyptian identity cards between Army guy’s fingers. Our fate is in his hands. For their part the very least it could mean is confiscation of their licences to work and with it, financial ruin. Things are hard enough as it is. A wave of feeling passes over me of the potentially grave consequences of little things, small incremental decisions. More immediately, what concerns me is that this seemingly nice guy could just be the ‘good cop’ prelude to a very long and unpleasant night…and whatever else to follow. This man has the power to make the lives of at least two of us take a significant turn for the worse.

But just at that moment I detect that the mood is lifting and there is a hint of a smile on our inquisitor’s lips. He tells me more about the military zone. There is a feeling of things starting to come to a conclusion. He asks us each to give our full names and enters them on the page of a desk diary. He has a bit of trouble with my name. “Tim”. “Cooper”. And what is my family name? “Cooper”. I suggest he takes it from my passport but he doesn’t seem to think it necessary. The passport and identity cards are returned to their owners. I notice Mohsen relax a little.

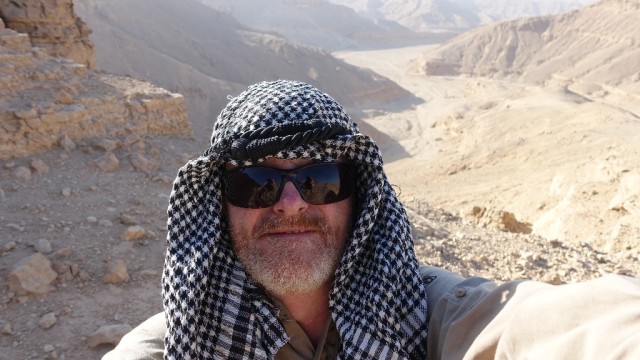

As I finish the tea, the army man addresses me directly: “Mr Kooba, please update your maps to show that this is a military area”. I assure him that I will. Things are quite chatty now, and I can see that my friends are smiling. It feels like it’s been about forty-five minutes to an hour, but I’m not really sure. As he beckons us to rise, I am now fully aware of being physically, mentally, and emotionally drained and I am taken by surprise when he asks us for a selfie before shaking my hand warmly, saying it was a pleasure to meet me, and seeing us off on our way. For my part, I thank him for the tea. I don’t need a passport to prove that I’m British.

Back on the road to Luxor things are quiet in the car to start with. We are all assimilating what has happened over the past two hours. I lean forward and tell the guys how sorry I am for getting them into this but they already seem cool about it. “Let’s celebrate at our favourite fish restaurant!” Hamdy enthuses, “It’ll be the best fish you’ve ever tasted!” Reluctantly I put this off till tomorrow. I am just too tired. My only thoughts now are of a shower and a bed. And sending messages to Pauline and Jenie. In the case of Jenie I also try to call her, but lose signal repeatedly. The message will have to do till now.

In the car, the earlier tension has relaxed and smiles break out. There’s a feeling of Thelma and Louise, but for guys. The cousins tell me the outcome could have been very different. All had been going quite well for the pick-up but when they set off to drive towards me they went up the wrong desert track and bumped into an army unit that included the man with the bulldozer. The army had already seen their flashing headlights and my light emerging from the desert and they were under suspicion of being the two fugitives involved in the recent shooting at Nag Hammadi; of being involved in antiquities theft from the valley down which I was walking; and of assisting someone to enter a military zone.

“We are lucky it was the army captain that questioned us and not his boss” Hamdy says gravely, to which Mohsen adds “And lucky that it was the army we ran into rather than the police. The police would not have been so kind to us”. The accusation of being the two gunmen was cleared up first as the guys’ ID cards showed they were from Qurna, not the same village as the suspects. “And the captain had been to school there, so he immediately felt friendlier towards us!” Mohsen laughs. As for the other two charges, these rested on my identity and motives. The guys had spent most of the interrogation convincing the captain that I was a “well-known British writer” on an expedition that I was going to write up in a book on my return to England. “That’s why he wanted the selfie!” Hamdy reveals and there are laughs and high fives all round.

Looking out of the window I can just see through the enveloping darkness that we are starting to turn the Qena Bend. Soon we would be getting closer to the Nile, then following the desert road back to our respective homes on the west bank at Luxor. I feel tiredness and emotion start to consume me.

It’s been a long day.

[Header image: When2Trip]